Jose Antonio Sanvicente, the infamous driver who ran over and left Christian Joseph Floralde, a security guard manning traffic along Doña Julia Vargas Avenue in Mandaluyong, can no longer be arrested by the Philippine National Police (PNP).

Jose Antonio Sanvicente, owner of the SUV that bumped and ran over a security guard in Mandaluyong City who later turned himself in, can no longer be arrested as of now.

— Inquirer (@inquirerdotnet) June 15, 2022

READ: https://t.co/ljX4c3wpzM pic.twitter.com/smIHw5aTGY

According to the PNP, the period to arrest the driver without a warrant has lapsed. The incident occured on June 5, and the limit for a warrantless arrest is only ten days. The PNP now claims that it’s in the hands of the prosecution to pursue any legal action against the assailant. Well, that is if they find any “probable cause.”

“Well in as far as the Philippine National Police po is concerned, we consider this case solved no, considering that we already filed the case and ’yon pong ating person of interest or the suspect voluntarily gave up to clear matters at hand. So we are now leaving to the prosecution’s office, to the courts, on the proper venue to answer the matters at hand,” said Lt. Gen. Vicente Danao Jr. in a press briefing on the incident.

The facts of the case (so far)

The hit-and-run incident went viral on social media, prompting senator-elect JV Ejercito to post a P50,000 reward for any information leading to the arrest of the assailant.

Putting up a P50k reward for any info regarding this evil and idiot driver who purposely ran over a traffic enforcer.

— JV Ejercito (@jvejercito) June 5, 2022

Really furious watching the video!https://t.co/1b4DgxN33v

The day after the tweet was posted, Ejercito received a message from an “emissary” of the accused that he will surrender to the police.

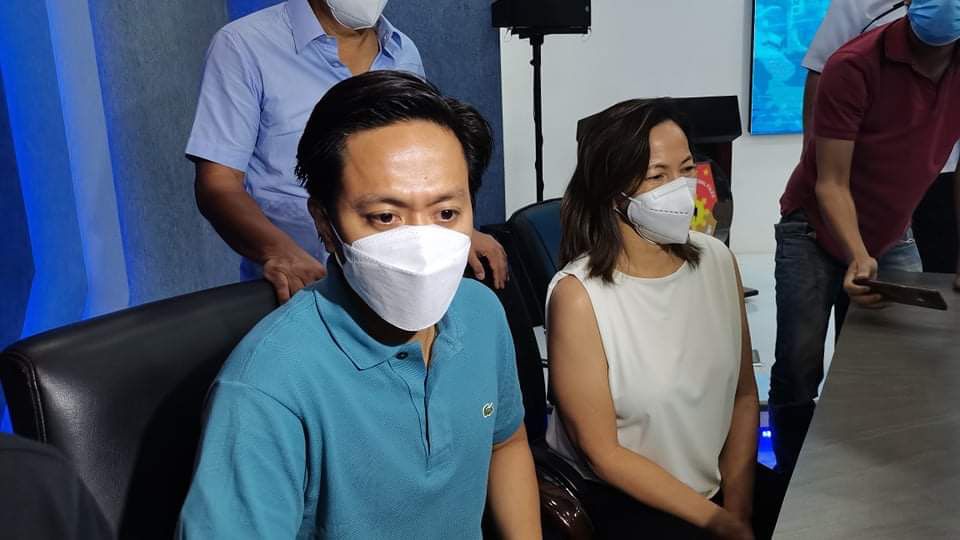

On June 15, Sanvicente and his family appeared in a press conference in Camp Crame to address the hit-and-run incident after surrendering to the police. Sanvicente’s mother had a lot to say.

“Syempre, hindi ho kami makatulog, hindi kami makakain, syempre anak namin ’yong involved, saka nag-viral na eh ’di ba. Masisira na ’yong buhay ng anak ko; for any parent ba gano’n ang gusto n’yo sa anak niyo?” she said in a statement during the press conference.

(Of course, we can’t sleep, we can’t eat, because it’s our son that was involved in the incident and it went viral, right? Our son’s life will be ruined; for any parent, is that what you want for your child?)

“Mabait ’yong anak ko, ano, nagta-trabaho siya, he’s a very responsible man. And I think ito, aksidente naman talaga ’to, lumaki lang nang lumaki. And I feel so sad kasi ano na mangyayari sa future ng anak ko ’di ba?” she added.

(My son is kind, he has a job, he’s a very responsible man. I think this is really just an accident, and it just got bigger and bigger. And I feel so sad because what’s going to happen to my son’s future?)

Prior to the surrender and press conference, the PNP failed to find Sanvicente after the incident or secure enough evidence to prove that he was the one driving that day. It’s also important to note that Sanvicente has had a record of three previous citations for “reckless driving” from 2010, 2015, and 2016.

The Land Transportation Office has permanently revoked his license after he skipped two summons from the office. Sanvicente is now barred from driving in the country.

A stark contrast

The leeway that the PNP has given Sanvicente is a stark contrast to how the accused are treated when they don’t have money. Days after the hit-and-run, on June 9, 91 farmers, advocates, and campus journalists were arrested in Tarlac on the basis of “malicious mischief, resistance and serious disobedience, and obstruction of justice.”

Shortly after, five foreigners and three others were released from custody, but the rest stayed behind bars. The remaining 83 individuals were released on June 12 after posting bail. There have also been allegations of abuse while they were detained.

LOOK: Activist farmers and land reform advocates hold a protest at the Department of Agrarian Reform to decry the mass arrest of more than 90 farmers and advocates in Concepcion, Tarlac. @BPinlacINQ | 📸: AnakPawis pic.twitter.com/gEl0ByZVtd

— Inquirer (@inquirerdotnet) June 10, 2022

The Commission on Human Rights has taken notice of the case and will investigate the claims of the accused and the PNP.

Unlike Sanvicente, the farmers and any of their advocates were not given a press conference or any significant airtime for them to plead their case to the public.

Same goes with the Piston Six during the height of quarantine. They were just fighting for their livelihood. Instead, they were faced with an almost immediate arrest and a week-long detention for some.

The contrast in treatment of Sanvicente, Piston Six, and the Tinang 83 is nothing new. Those who cannot afford to delay “justice”—or escape from it entirely—have always been on the losing end. The Sanvicente hit-and-run case should have been a textbook example of a clean arrest. Instead, lapses in action and media mileage were the order of the day.

Is justice actually blind?

The dramatic press conference after hiding for ten days—just enough time to escape the time limitation of warrantless arrests—is exactly what privilege looks like. Those with means can buy their time around justice or even bend it to their will, or even call for a press conference to “publicly apologize.”

Instead of facing the consequences of their actions, they have the justice system on speed dial, ready and willing to hear them out. Due process and human rights suddenly mean something when you drive an SUV.

Same goes for the yet-to-be punished Poblacion Girl. It’s been months since Gwyneth Chua breached quarantine protocols to party, but the last news article about her was about the Makati City Prosecution Office just recommending filing a case against her.

If it was a jeepney driver who ran over the guard, you think there would have been a press conference?

— Ted Te (@TedTe) June 15, 2022

It begs the question, what if these people didn’t have financial means? What if Sanvicente was just a jeepney driver, like what lawyer Ted Te said? Or what if Gwyneth Chua just broke quarantine to buy necessary goods like food or medicine?

Well, we know the answer to that question.

The scales of justice need to be balanced. The reason why the symbol for justice is a weighing scale is because it’s not supposed to favor one side over the other. Fact and evidence are supposed to be the basis of justice and not influence or wealth. But in all truthfulness, that is not the case.

It’s incumbent on the government to make sure that justice is actually blind—and not peeking from under her blindfold at the behest of anyone. It’s tough to say that tangible change will occur in our lifetime, but it’s also incumbent upon us to make enough noise and demand for it.