The camera follows Rosa along the now tranquil streets of the metro. Having spent a whole day in the company of corrupt cops, she walks tirelessly. The handheld camera follows her without respite, almost reflecting her convoluted thoughts. She arrives at her destination: the house of a loan shark. Although beaten by stress, Rosa maintains her fierce, resolute composure as she persistently asks the man if she could pawn her daughter’s phone to him.

As she walks back to the precinct, her neighbors taunt her for “ice.” She approaches a fishball stand, totally disrobed of her pride. For once, the unsteady camera focuses on Rosa as she gorges on the skewered squid balls. With every hurried bite, her eyes swell until tears run down. The night has fallen, but for Rosa, another day full of uncertainties is about to unfold.

Without any definite conclusion, the film fades to black and the credits roll.

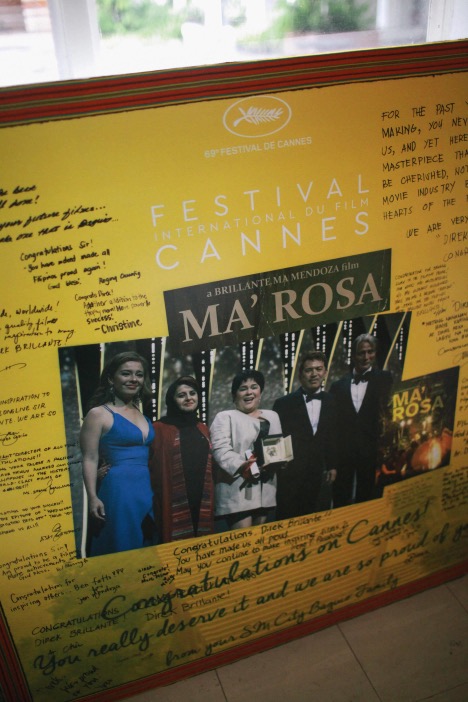

That scene is how internationally acclaimed director Brillante Mendoza ended his most recent film Ma’ Rosa, which bagged the Best Actress Award from Cannes Film Festival for Jaclyn Jose’s subtle yet poignant performance as a drug dealer in an impoverished community.

Mendoza’s films ponder on the plight of marginalized people and communities. Ma’ Rosa, for instance, shows a day in the life of a family fighting against corrupt policemen. His characters inhabit a world familiar to the audience, sharing a similar plight to those of Lino Brocka’s. More than that, the scenes Mendoza creates in his films are from the same world we inhabit. “Film, for me, is a reflection of life. How I see life, how I experience life [is] how I want my films to be,” he explains.

Throughout the years, Mendoza has developed an aesthetic akin to that of a documentary film, or an “eyewitness account,” as described by director Quentin Tarantino after seeing Kinatay. True enough, Mendoza’s portfolio is stripped of the glitz of most movies, replaced with the grit of real life. With shots that are rarely stable, he creates an environment for viewers to take in the film as curious observers, and to some extent, as voyeurs.

Mendoza and screenwriter Bing Lao, a constant collaborator, employ a thought process called the Found Story method. In a nutshell, the Found Story method finds its reference in real-life circumstances involving real people. It requires rigorous research that takes months to finish; research and the script for Captive, which stars French actress Isabelle Huppert, took more than a year to finish. While the process seems daunting, it provides a rather eye-opening perspective towards life. “When you discover these [stories], it’s not only about the film but the experiences [of] the real people you’re dealing with.”

The Found Story method applies to all aspects of his films. For one, Mendoza requires his actors to immerse themselves in the communities where the stories are based from to achieve authenticity; Nora Aunor had to learn the techniques of facilitating childbirth for her role as a barren midwife in Thy Womb. On the set, Mendoza does not give his actors a complete script. Instead, he only reveals the situation and allows them to churn out the scenes. “When I give the situation to the actors and they know their characters, they deliver an acting that is spontaneous and authentic.”

Mendoza’s method of production is as sensitive as the stories he deals with. For instance, the production of his crime thriller film Kinatay had endangered him and his actors. “We were almost shot because there was this group of [cops] in Cavite who thought the film was for real,” he reveals about the shoot that happened at two in the morning. For Thy Womb, he filmed a live birth.

With stories that put his life in danger, the director seems to fear nothing. According to Mendoza, “the only fear that I have is for my producers.” With a lot of trophies and medals from prestigious award-giving bodies like the Locarno (where he won the Golden Leopard in 2005 for his first film Masahista), Cannes (where he won the Best Director Award for Kinatay in 2009), Venice, and Berlin Film Festivals, it is ironic that he still needs to worry about the business side of his films.

The night before our interview, Mendoza had posted on social media that Ma’ Rosa was on the brink of getting pulled out from cinemas. A day after the interview, several cinemas no longer showed the film; the win Filipinos reveled in did not translate to viewership. “They appreciated only the win, because not everybody is interested in film. They’re interested in ‘nanalo siya’,” Mendoza says with apparent forlorn.

The abundance of independent film festivals in the Philippines may suggest that independent cinema is thriving. However, for Mendoza, the Filipino film audience has only reached a certain state of “awareness.” “Let’s face it, we are not film educated.” Although he has acknowledged that his films are quite difficult to comprehend for those who consume movies for entertainment, he also realizes that most of the Filipino audience are just not fond of the films he makes. “Film is an art and you cannot expect everyone to appreciate art,” says Mendoza. “You just have to accept that [this is] the audience that you have. We cannot do anything about it.”

While choices in film are an acquired taste, Mendoza says that exposure to good films, “something that will provoke critical thinking at a young age,” will instill a better understanding of film to the audience. Mendoza, who had attended a public grade school, finds that the Philippine educational system does not give the arts the same amount of importance given to math and sciences. “Art, in general, should [be taken] seriously as early as elementary.” He also believes the establishment of dedicated local art house cinemas is a means to create a wider audience.

Mendoza might not have filled cinemas in the Philippines, but he has found avenues to share the unheard stories of Filipinos to other parts of the world. “The audience was very serious about film, about the craft,” he recalls of his encounters with foreign viewers abroad. He admits that while he has developed a local audience, it will take some time before it grows. “And this is the audience that matters to me.”

In Serbis, Mendoza takes the audience to an old, forgotten cinema in Pampanga where men enter not to watch but for extra service. Without an audience, the future of Philippine cinema might lead to a similar state. But despite the challenges he faces, Mendoza wouldn’t let this happen, “For as long as I can, I’ll do films of this kind.” “Brillante” is an unusual name that connotes value. For Mendoza, his gems are not the shining trophies or medals he receives; they’re the values he finds in the stories of the unheard.

This article originally appeared in Northern Living, August 2016.

Writer: OLIVER EMOCLING

PHOTOGRAPHY JAKE VERZOSA