It’s been over a year after the Me Too movement exploded. Originally formed in 2006 by activist Tarana Burke to help POC women who’ve suffered from sexual abuse (coinciding with her nonprofit for the same cause, Just Be Inc.), the name came from the answer Burke regretted not saying to a thirteen-year old girl who had confided to her about her own sexual abuse (“Why couldn’t you just say ‘me too?’” Burke chastises herself).

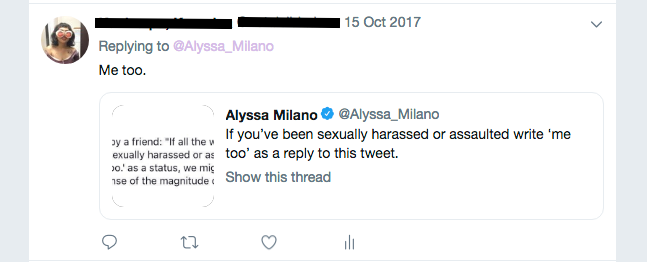

In 2017, the movement sprung in full-force when actress Alyssa Milano posed a simple call to action to her Twitter followers: if you’ve ever been sexually assaulted, reply with “Me Too.” She had posted this in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein scandal, when a New York Times report exposed the once-powerful studio exec’s sexual harassment cases. The scandal that sent ripples through the world: after Weinstein was many others.

I remember when the report came out. Reading the article in pauses. Sending it to everyone I knew. Discussing it with my old boss over lunch. “Do you know what makes it even more powerful? That the reporter who wrote about it is Woody Allen’s son.”

I remember, too, when Alyssa Milano first tweeted Me Too.

If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet. pic.twitter.com/k2oeCiUf9n

— Alyssa Milano (@Alyssa_Milano) October 15, 2017

I read that, and my hands hovered over the keyboard. I typed and deleted an answer, closed the window, opened it again, retyped the same words, doing this over and over again, afraid of coming out but also of letting the moment slip (why did drafting a single dumb tweet feel this monumental)—

“Me too,” I finally replied.

~

I’ve mentioned these before, but there’s this statistic I’ve clung on to ever since I came across it in a Catherine MacKinnon journal article. In 1989, the feminist scholar wrote that only 7.8 percent of women will not experience any kind of sexual abuse or harassment in their lifetimes. This was over 20 years ago, and based in the U.S., but it still rings true. After all, in 2016, the Center for Women’s Resources reported that one woman or child in the Philippines is raped every 53 minutes.

Want to hear something sad? When I read that, my first thought wasn’t, “oh no, only 7.8% of women won’t be harassed?” but “who are these magical women who don’t get to experience it and how can I live with them?” A variation of that was also said by my female friends when I told them about it.

Here’s the thing: sexual abuse is incredibly widespread, but because of the silencing effect it has on its victims, you wouldn’t know it. People don’t speak up about it in part because (1) for many, speaking up may be detrimental for them (if your father sexually assaulted you and your mother sides with him, chances are that you’ll be forced out of your home), and (2) because of huge shame that society imparts on to victims, the depths of which is far greater than sexual abuse’s reach. You may spend years and years being with someone and never know that they ever experienced it.

As a feminist, this was something I knew intellectually, and yet this information offered no comfort or protection when it happened to me. I lied to my friends. I was trying to deal with the bureaucracy so I wouldn’t have to see my assaulter every week (which itself was a very traumatic process), but while that was happening, I wasn’t able to tell my friends the whole story. I would tell people I had been assaulted and see the relief on their faces: “assault” wasn’t predicated by “sexual.” I was a hypocrite. Publicly, I would tell people that no sort of sexual abuse was ever the victim’s fault. But when I would be alone in my room, I would burn cigarette holes into my arm to punish myself, or at least to expunge the guilt that wasn’t mine to bear. I couldn’t tell people that it happened. I couldn’t tell people that it wasn’t the first time that it happened, and the trauma of this was bringing out everything I was repressing from that. I just couldn’t.

But there is strength in numbers. When the #MeToo movement swelled, less than a year after my assault, I felt, for the first time, that I could talk about it. For many, seeing so many people speak out made you feel like you could speak out, and seeing Weinstein fall made you feel like your Weinstein could fall, too. There’s a huge ripple effect on reporting whenever a rape case gains visibility and is successful in bringing down the assaulter. The number of people (overwhelmingly female, because let’s face it, the common victim is a woman) who report their cases dramatically surges. This happened in India. After the Nirbhaya Gang Rape scandal took over the nation, more and more women started reporting their cases.

But there is strength in numbers. When the #MeToo movement swelled, less than a year after my assault, I felt, for the first time, that I could talk about it. For many, seeing so many people speak out made you feel like you could speak out, and seeing Weinstein fall made you feel like your Weinstein could fall, too. There’s a huge ripple effect on reporting whenever a rape case gains visibility and is successful in bringing down the assaulter. The number of people (overwhelmingly female, because let’s face it, the common victim is a woman) who report their cases dramatically surges. This happened in India. After the Nirbhaya Gang Rape scandal took over the nation, more and more women started reporting their cases.

I know many people struggle with understanding this. When someone speaks out and many join in to add their own stories, it’s easier to believe that these people are lying. That is, if you’re not a victim. If you are, you’d understand that many people have their own stories that they’ve been sitting on, and also just how long someone can sit on one.

Many of the famous #MeToo stories lived on as open secrets, ugly gossip, “baseless rumors” that appeared in Page Six blind items before the movement shone a bright light onto them. Andrew Rapp’s experience with Kevin Spacey, for example, was something that had been floating on the Internet for years, mostly on Tumblr, only both parties were never named in respect to Rapp. If you were part of the community, you’d know.

It’s a pretty common thing for cases like these to proliferate as open secrets. As the Ateneo case a few months ago uncovered, there are many instances of institutions finding out that they are housing an abuser and not doing anything about it, letting his status as an abuser live on as an open secret. I know a college professor who’s almost legendary in how much people know about his harassment cases, so much so that everyone in his department knows about it, and yet he’s barely faced any repercussions. I know this because when my friends reported him, he got a slap on a wrist, nothing more.

I think what angers me the most about that is how traumatic reporting is to any woman. Joi Barrios has a poem about how reporting a rape is just like another rape (the poem’s translated form went viral a few months ago):

‘RAPE’ by Joi Barrios.

Kinilabutan ako. pic.twitter.com/DYdZ8iFlPd

— Menchani Tilendo (@menchongdeee) September 28, 2018

I recall one day when I was trying to get away from my assaulter, and had basically been told that I had to get over it. I had class right after. I remember being numb, sitting in class, and then suddenly not being numb, and running outside the room and crying. Crying in the hallway, crying in the comfort room, crying as I entered a stall, and crying when I called my best friend and she asked frantically what happened until I finally managed to choke out, “Berch, CR, Please.”

“Isn’t this such a girl thing to do,” she said ruefully after she arrived and I explained to her in tearful fits what happened, “crying in the comfort room because the system just failed you?” That was my first laugh of the day.

~

Every movement, especially when it’s centered around women, faces a backlash. As soon as the movement surged, the cries of witch hunt soon started. People calling out abusers were accused of singling them out. Many editorial outlets released op-eds about the men rightly or unfairly accused and how they got through it, doing so at a pace far quicker than they were releasing stories about the women who came forward.

A few months ago, someone I knew wrote about how much of a witch hunt the Ateneo case devolved into. “We need to see proof before we judge,” she said. I read that and felt like she had thrown a brick at me, hitting me right at the face. I didn’t need to see proof because it happened to my friends, to me. We were the proof.

Dr. Christine Blasey Ford spoke about how Brett Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her when they were in high school. She was eloquent and composed as she told the court in full detail what he did. He was still made a US Supreme Court justice.

OK, so…do you FINALLY fucking understand why women don’t report their sexual assaults? Do you now get it? DO YOU?

— Tomris Laffly (@TomiLaffly) October 6, 2018

Every time I have to tell my friends that their voices matter and that they should report, I mean it less and less. Speaking up is a deeply harrowing experience: it involves carving out our pain and trauma, hammering though the deep walls our minds have created to keep us safe, and lying naked in front of the public’s eye as they take in our stories, knowing that every sordid detail is playing out in their heads—and for what? To not be believed? Or to be believed but to see your abuser get away, anyways? My belief in the system crumbles more and more each time someone I know personally comes forward and is then spit out by the legal process. How many of my friends will I have to listen to talk about how a man violated them, and how violated they felt trying to report that man? Will I have to do the same again, too?

A year after #MeToo, and the answers remain grim.

Like this story? Subscribe to our newsletter here to receive similar stories.

Read more:

Picasso’s $115 million naked girl painting and its place in the #MeToo movement

#MeToo and #HowIWillChange, the conversation we needed

A “major” sponsor’s sense of entitlement puts Miss Earth pageant on the spot

Read more by Zofiya Acosta:

The physical labor of beauty

Who’s afraid of the contractual workers?

Writing a nation: Should we start using Baybayin again?

Writer: ZOFIYA ACOSTA

ART TRICIA GUEVARA