It’s ironic, isn’t it, that whenever press freedom is threatened that it’s also the time we need media the most? And not just the press—in times of tyranny, we need everyday citizens to use whatever platforms as possible to inform and fight back.

You probably know by now about the latest development in the ongoing battle to shut down the country’s biggest broadcasting network. Here’s a rundown: ABS-CBN’s 25-year franchise, which is a government-approved contract that allows its operations, is going to end on Mar. 30. President Rodrigo Duterte has repeatedly stated that he will not allow the franchise to be renewed. On Feb. 10, Solicitor General Jose Calida filed a quo warranto petition to the Supreme Court to revoke its franchise, accusing ABS-CBN of violations and citing alleged unethical business practices and foreign ownership.

Don’t be fooled though: The attempt to shut down ABS-CBN is a thinly-veiled attack on press freedom. “This government is hellbent on using all its powers to shut down the broadcast network,” the National Union of Journalists in the Philippines (NUJP) declared in a statement. “We must not allow the vindictiveness of one man, no matter how powerful, to run roughshod over the constitutionally guaranteed freedoms of the press and of expression, and the people’s right to know.”

History repeating

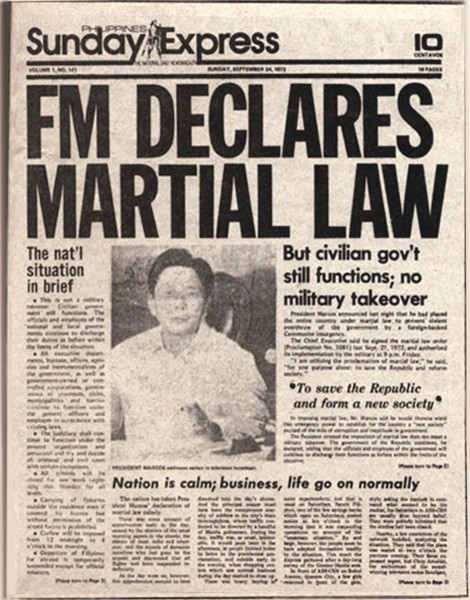

This isn’t the first time however that the local press has been the target of a coordinated attack. As a matter of fact, the current situation mirrors the actions of former president and dictator Ferdinand Marcos. During the Martial Law era, journalists’ rights to publish freely were stifled. On Sept. 28, 1972, Marcos issued Letter of Instruction No. 1, which authorized the military to take control of assets from major media outlets including ABS-CBN, The Manila Times and Daily Mirror among others.

In an act of resistance, journalists who protested against Marcos created their own underground press such as the Taliba ng Bayan, Ang Taong Bayan, and Tinig ng Masa, all of which boldly distributed in marketplaces or school campuses. When the government took notice, it began to track down these journalists. Liliosa Hilao, the 23-year-old editor of Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila’s school paper Hasik and a member of the College Editors Guild of the Philippines, wrote actively against Marcos and became one of the first victims of the crackdown.

The attacks on the press

With the resurgence of Martial Law-era tactics, the current administration is improvising efforts to silence the press. The President has consistently vilified the press, implying that the media have been purveyors of false and vile materials. “Just because you’re a journalist you are not exempted from assassination,” Duterte said in a press conference in May 2016. Duterte then acted against online news platform Rappler by insinuating that the media organization was not completely owned by Filipinos. Contrary to his allegations, Rappler is fully owned by Filipinos, and has only righteously engaged in partnerships with foreign companies in order to raise capital abroad. In addition, Rappler has been transparent with its corporate filings, which are available online.

The President also has a long history with ABS-CBN. In 2016, the network aired a 30-second ad that criticized Duterte. “We are duty bound to air a legitimate ad,” the network stated in its defense, stating that the ad was also compliant with Commission on Elections laws. In 2017, during a speech in Marawi, the President called out ABS-CBN and the Philippine Daily Inquirer. “Ako lang ang presidente na bumibira ng Inquirer pati ABS-CBN. Binababoy ko talaga. Kasi alam nila basura eh,” he said. That year also saw the first instance of the President declaring that he wasn’t going to renew the broadcast network’s franchise, stating that the network had swindled him by not playing an ad he allegedly paid P2.8 million for. He then accused ABS-CBN of estafa. In 2018, the President once again claimed that he will not be renewing its franchise and repeatedly aired his threats throughout 2019.

NUJP has called the President’s actions vindictive, and for good reason: The move not to renew the network’s franchise is influenced by a personal vendetta of a president who goes out of his way to attack the press and use his administrative powers to shut down media organizations that criticize him.

It’s also not a surprise given Duterte’s past. In 2003, Jun Pajadora Pala Jr., a radio journalist and political commentator who was a staunch critic of Duterte, was killed shortly after publishing a report that accused the then-mayor of corruption. In 2016, one of Duterte’s alleged former hitmen testified that Pala’s death was ordered by the President. The alleged leader of Davao Death Squad Arturo Lascana backed him up. And in 2019, a total of 13 journalists have been murdered under the Duterte administration.

Defending the Fourth Estate

It’s important to remind ourselves why we need the press. A cornerstone of a democratic society is a free press. Aptly called the “Fourth Estate,” the press serves as a system of checks and balances of a country’s people and its government. Through the press, we learn how to form our own opinions and decisions based on news, commentaries and stories they publish. It is with this information that we prevent ourselves from being deceived by propaganda. When we lose the freedom of the press, it curbs our own freedom of expression, our right to information.

It’s important to remind ourselves why we need the press. A cornerstone of a democratic society is a free press. Aptly called the “Fourth Estate,” the press serves as a system of checks and balances of a country’s people and its government.

Suppressing press freedom includes any act of hindering the press from candid reportage, whether it be through television, print or online. In addition, a possible shutdown of the country’s biggest media outlet entails employees losing jobs, making this an issue that concerns not only journalists, but any Filipino citizen as well.

With an impending threat as big as this looming over the country, the press should be called to band together. The current system that the media follows, one in which we view each other as competitors, doesn’t work, especially when we’re all being attacked. What good is competition when we’re being shut down one by one? When journalists from all outlets are being threatened? The President doesn’t care about the lives of journalists: As previously mentioned, he publicly stated that being a journalist doesn’t exempt you from assasination, whatever that means. Let’s not forget that the Philippines is the site of the deadliest attack on journalists in history, with a total of 34 killed in the Maguindanao massacre. Even outside Duterte, the country is a dangerous place for journalists.

When we lose the freedom of the press, it curbs our own freedom of expression, our right to information.

At the same time, everyday citizens are also called to take it upon themselves to protect democracy. The prospect of citizen journalism then arises, in which citizens have the opportunity to contribute in disseminating journalistic values.

By sharing opinions, ideas and experiences to the general public, we start a conversation about the government and what it does for its people. Our own freedom of expression is an aid to the freedom of the press, and if the administration continues to lash out on professional media outlets, then it is our duty to withstand threats to our democracy.

Losing freedom of the press means losing one of the final comforts left during a time of tyranny: That even if the government isn’t protecting its people, there are individuals risking their lives to speak out against injustice. Losing this is a win for tyranny—and the people need to unite to make sure it doesn’t happen.

Header photo courtesy of Edwin Bacasmas from Inquirer.net

Get more stories like this by subscribing to our weekly newsletter here.

Read more:

How the Philippine media is threatened over the years

Sotto law now covers broadcast and online media

This story book chronicles the dreams of Kian Delos Santos

Writer: THEA TORRES AND ZOFIYA ACOSTA