After hosting the quite controversial Southeast Asian Games, what is left of the equally contentious space that is New Clark City in Tarlac? After the P55 million cauldron’s fire has died down, the reality is that the smart city, like most promising structures in the country, will be controlled by the private sector.

But that’s not all bad news. Like the inclusive smart city it promised to be, the New Clark City still have glimpses of hope.

A village of domes

The complex’s river zone, for one, hosts an altogether diverse landscape. In lieu of newly-constructed structures, the grass patch remains, as well as some newly planted trees. The 4.5 hectare River Park is home to a series of art installations, one of which is by the artist Bernando Pacquing: a village of natural domes constructed out of century-old, reclaimed, endemic hardwood—molave, guijo, yakal.

Inviting as these natural structures are, they are also interrogations in space, an inherent curiosity that Pacquing has been known for. Like most installations in the area—from Bea Valdez’s metal structures to Kennet Cabonpue’s rattan viewing pods—Pacquing’s domes invited interaction.

There are six structures in total, each made with distinct elements thus different from one another: the 10-Sticks Dome, Coral Dome, Natural Dome, Mangrove Dome, and Geodesic Dome—all are connected through hanging bridges reminiscent of sea-bound Badjaos’ settlements.

The Tarlac-born artist’s fascination with domes begun in 2009 and was influenced by various natural and man-made architectural marvels around the world from the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem to termite mounds in Africa.

Found objects are also a strength of Pacquing’s. Most of the parts from these domes, including his first dome in Davao, are driftwoods and reclaimed hardwoods from old houses, adding another depth and sense of history to his works—that is apart from the apparent messages that a viewer or an interactor with the art can immediately deduce: resilience and interconnectedness.

Displacement and belonging

But not even an influx of art installations can cover up the news of indigenous peoples displacement has risen from under covers, revealing the secret of the smart city for the world to know.

“On the outskirts of the proposed and ongoing construction of New Clark City in Tarlac bordering Pampanga, are the ancestral lands of the Aetas. What was once a peaceful place where farmers and tribes could plant food and roam around freely—a place where they could be with nature and with their own nature—has since been bombarded with trucks and bulldozers for urgent reformation a hosting site for a multisport event and ultimately, a utopian metropolis,” writes one of our staff writers regarding the issue.

[READ: The Aeta displacement was the first red flag to all of this #SEAGamesfail]But another perspective has soon risen after the cloud that is the SEA Games issue has dissipated. The local government insists that no ancestral land has been infringed upon and that those who were displaced have been compensated accordingly, some even finding gainful employment from the construction of the New Clark City. “What’s apparent from these conflicting reports,” a writer for a local publication says, “is that there are Aetas who are happy, and there are Aetas who aren’t.”

A truly inclusive public space

In the same feature story, an interview with the principal architect of the sports facilities in the New Clark City, writer Audrey Carpio detailed the mis en scene of the day their team went about the recreational side of the development.

“As we strolled down the path, we spotted workers having their lunch inside a grove of bamboo trees, Aeta families picnicking on the slopes, and the occasional guy snoozing in a hammock,” she wrote.

These are truly scenes that get one to thinking of the park’s inclusivity and effectiveness. Can urbanized spaces ever be reclaimed? Can recreational parks ever have a space in the landscape of urban development where malls and high-rise residentials are favored?

I compare this to writer Jenny Odell’s reflections on the Morcom Rose Garden in Oakland, California, of its defiant existence, its appeal that lures people to stay awhile, and of attention-holding structures in general. It’s rare that spaces themselves can wield this power, but the incorporation of art makes it possible.

Pertaining to various public works of art, Odell writes, “In each, the artist creates a structure—whether that’s a map or a cordoned-off area (or even a lowly set of shelves!)—that holds open a contemplative space against the pressures of habit, familiarity, and distraction that constantly threaten to close it.”

Pacquing’s domes may just be that binding structure that the New Clark City needs.

Header photo courtesy of Silverlens Galleries

Get more stories like this by subscribing to our weekly newsletter here.

Read more:

The Manila City Library is proof that public spaces aren’t priority

Everything you need to know about Art Fair 2020

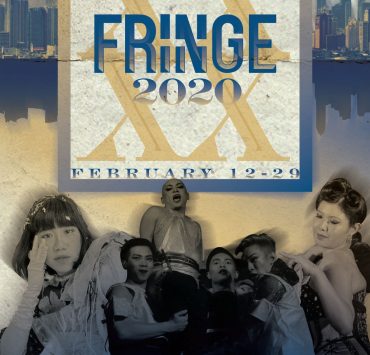

A Valentine’s vogue ball, archival film viewing, and more at this year’s Fringe Manila Festival

Writer: CHRISTIAN SAN JOSE