“There was a girl one time who walked up to me while I was next door [at Pineapple Lab] and told me: ‘I always come by your shop and it’s always closed.’ She was mad so I ended up opening the shop just for her.”

Glorious Dias is one of those places that looks really nice on the outside with its window display of barongs, silk tops, and various potted plants. But it is also the type that rarely opens. At least that’s how it seems to passersby.

On a Monday afternoon, Jodinand Aguillon opens his shop yet again just for one customer: me (and our photographer). His pop-up named after Miss Universe 1969 Gloria Diaz opens only on Thursdays til weekends. Officially. The rest of the week he is busy sourcing new old clothing to hang in his store adjacent to the experimental art space, Pineapple Lab.

His haul is usually the subject of his social media posts. That and his quest to restore them to their old glory by handwashing.

“I usually gravitate towards silks, pinya, and cotton mostly because they are more appropriate to the weather here,” Aguillon says as he flips through hanger after hanger of white or beige women’s tops. He washes each article by hand as most are made of delicate fabric. Though, he admits, it isn’t always as easy as lightly scrubbing them to rid of spots. In fact, most of the tops on display still have some stubborn stains on them, something Aguillon considers to give them an authentic vintage vibe.

On top of the women’s rack is a clothesline where some deadstock barongs he’s acquired from a factory are hanging. He’s redesigned some of it to make it more wearable by dyeing it with local dyes and shortening its sleeves. But even by itself some of this traditional men’s formal wear are, in Aguillon’s words, “glorious.”

Unlike the usual barong which only has embroidery on the front specifically from the collar down to the navel, these ones are fully embroidered, front and back and in every space available. Some of it also has front pockets for added utility.

This rack is the only permanent collection in his shop. The rest—the ready-to-wear selection—either gets sold quickly and replenished with new stocks or shuffled on different racks. These include an assortment of jackets (bomber, denim, tailored, varsity, etc.), beaded tunics, kimonos, jumpsuits, embellished tops, dresses, and jeans on a separate rack by the entrance.

Some of it were hauls for his previous styling gigs. He’s styled theatrical plays like Sa Wakas and Lungs but prior to moving back to the Philippines for a residency at Pineapple Lab in 2016, he was the creative director Toronto-based dance collective Hataw. He’s done productions for the folk dance group and styled dancers with references from Filipino pop culture and folklore.

When asked what pieces he is most fond of, he quickly went scrambling to the door leading to the back of Glorious Dias. Boxes upon boxes of inventory occupy the room: accessories, dresses, more barongs. It was only then that I found out that the real treasures of this vintage shop are hidden away in the storage.

He pulls out a cardboard box from a pile and begins unloaded its contents. “These are mostly Filipinianas, ternos, and vintage dresses I got from friends and people who come here with around 100 clothes from which I only get 10. Other times I just say yes even when most of it is nearly destroyed,” he says.

A red terno with its butterfly sleeves still intact is laid out before us. And then another one with intricate beading which he estimates to have been made in the ’80s. “I’m collecting these but I only have a few handful, some of them in dire need of restoration. Hopefully one day I will have enough to display on the shop or even a museum,” he jokes.

“When I have conversations about what vintage fashion is—especially to the Philippines—I think there’s a way to be proud of it again and to appreciate our designers and their artistry because it’s so impeccable.”

“I even have a Valera. I just can’t remember where I put it.”

I was astounded by the mere mention of the name of Ramon Valera. His work in modernizing the terno and its sleeves is the stuff of history. In fact, Valera was the only National Artist conferred for fashion design in 2006.

Since his death in 1972, there have only been a few retrospectives for his creations including one held at De La Salle-College of St. Benilde’s School of Design and Arts Gallery October last year, which is considered to be the first major exhibit of its kind.

Aguillon’s search of the Valera dress continued. He swore he stored it inside one of the boxes in the back but it would take the whole day to go through everything. He decided to put it off for another day.

But his search wasn’t actually fruitless. Upon unboxing, he’s brought out a few equally exquisite frocks with stories of their own. One of which is a hand-painted pinya Maria Clara striped dress with a matching top by Patis Tesoro (Pret-a-Patis, as he calls it).

It was still in pristine condition with no visible discoloration in the details. However, part of the reasons why he still hasn’t put it on display, as with the rest of his small collection, is because he’s still figuring out the best way to wash it by hand. “I don’t trust the dry cleaners. I do everything by hand,” he quips. Given the age of these dresses, washing it may even cause it more damage.

“What I do is I treat it with hugas bigas or rice water. It strengthens the fibers, makes it less prone to breakage.” Other times, when the garment is already damaged beyond repair, he finds ingenious ways to repurpose them.

Other stuff he’s unearthed in his search for the Valera, are two vintage Inno Sotto couture dresses made for young girls. Although their hues have faded, the details in them are still noticeable from the dull shine of the satin to the pleated petticoat underneath that slightly runs past the hem.

He pulls out one last dress from the box, a wedding dress. It’s a sleeveless dress with a round neck and a plunging back, adorned with butterfly beadwork. It came with the wedding ring pillow used during the ceremony when it was worn. On it are the names of the bride and groom and the year they were married embroidered on silk. It was designed by the late Pitoy Moreno.

“You know what, I realized just now that all my favorites are not actually on display. I have to work on that,” Aguillon says. He admits that part of him actually finds it hard to let go of these things, which in his opinion should be in museums for everyone to see, or at least in someone’s archives where it can be restored and cared for.

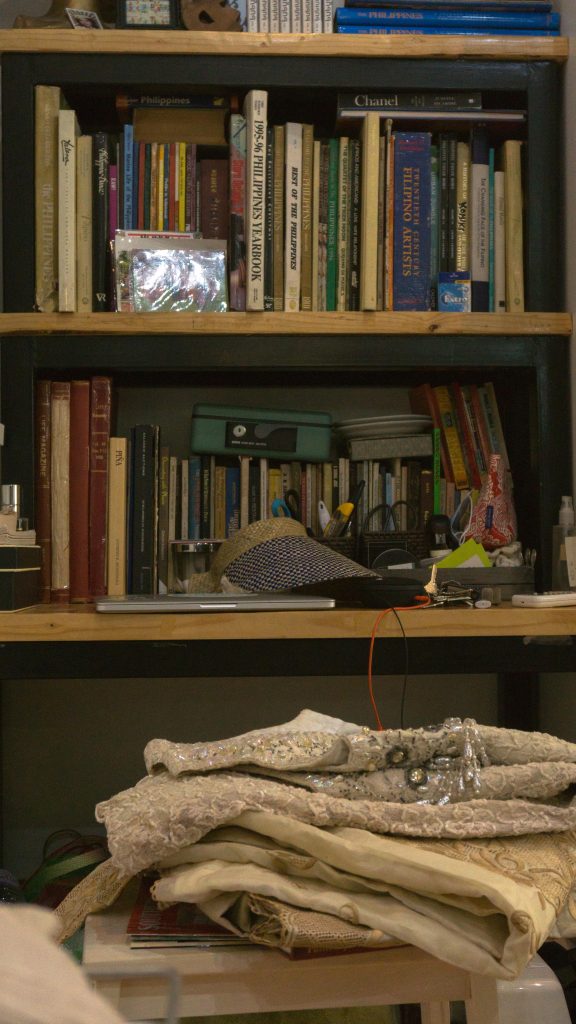

“There’s so much self-education that I still have to do on researching designers,” he adds. Validating whether or not the pieces he has are indeed by these Filipino designed by cross-checking and comparing details has inevitably become part of his process. On one corner of the shop is his library filled with his trusty references: books on Filipino fashion, designers like Valera and even a Cultural Center of the Philippines-published book on terno dressmaking.

“This is the stuff I get excited about. And when people incorporate these pieces in everyday life, that’s where the magic happens. But then when I have conversations about what vintage fashion is—especially to the Philippines—I think there’s a way to be proud of it again and to appreciate our designers and their artistry because it’s so impeccable.”

He has to leave for a meeting, he says. We thank him on our way out as he closes Glorious Dias’ door.

“I have to go and close it before someone comes again asking me to open the shop just for her,” he jokes.

Glorious Dias is located at 6053, R. Palma Street, Brgy. Poblacion, Makati

Read more:

The terno is not our national dress—but it could be

Why Poblacion’s gentrification is problematic

Legacy of Nat’l Artist Ramon Valera continues with his family’s new bolero designs

Read more by Christian San Jose

The terno is not dead. But new designers are killing it

Meet the Filipino architect reimagining domestic space in Hong Kong

The pitfalls of reimagining the baro’t saya

Writer: CHRISTIAN SAN JOSE

PHOTOGRAPHY TRICIA GUEVARA