I recently saw a tweet that made me laugh. It went something like: “Why do we always depict Bonifacio in a camisa and red pants? He wore a suit! And if he knew that BGC was named after him, his fancy a** would be so happy.”

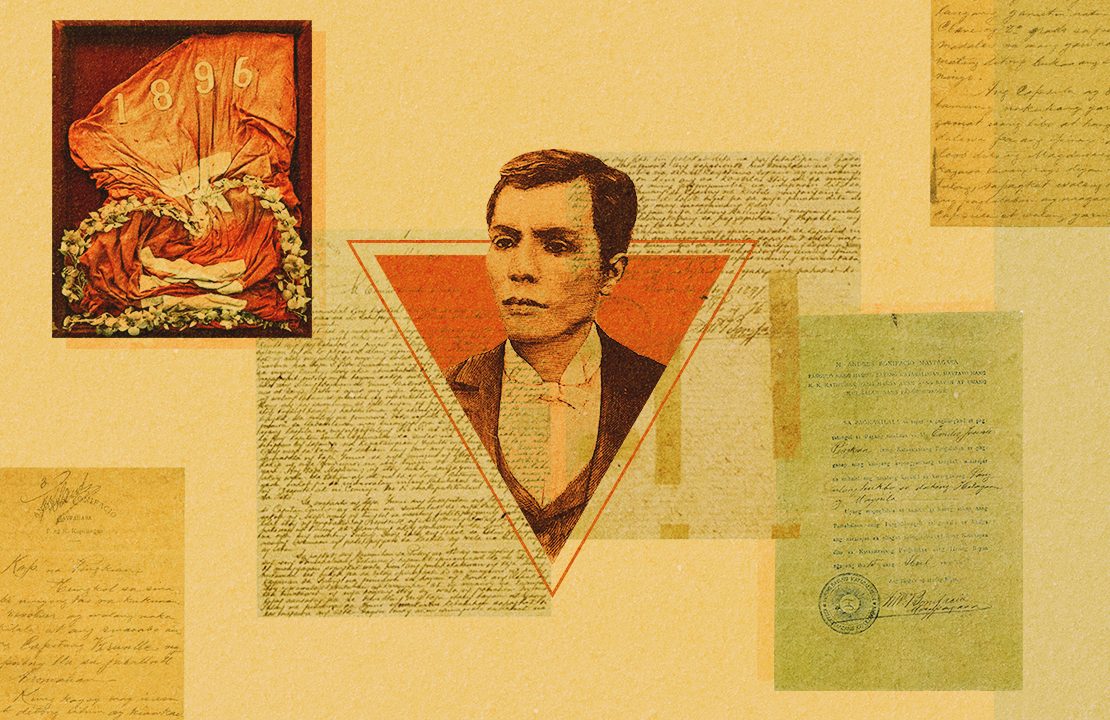

That got me thinking. I have never once seen a photo of Bonifacio—or the Katipuneros, even—in red pants. And the only official portraits of Bonifacio I have ever encountered showed him in a nice suit, complete with winged collar and tie. And this is based off his only surviving, badly faded photograph.

Now, consider his life story. Crudely put, he was a city boy, born and raised in Manila. His family was middle class, at best–not poor as many imagine him to be. He worked as a sales agent and warehouseman for what we today might call a multinational company. He even became a member of the Freemasons and of Jose Rizal’s La Liga Filipina.

But why has the camisa-red pants-bolo ensemble become his “brand”? What other aspects of the hero had been twisted by “history” and popular culture?

Red, the blood of angry men

Let’s start with the most striking aspect of his “look”—the red pants.

Logically speaking, I don’t think he would have worn red much. It’s just too eye-catching. In a time of revolt, when you’re trying to evade and surprise the enemy, something as loud and bold as red just begs unwanted attention.

This is despite red being associated with war, blood, and passion. That’s why it’s understandable how the color became tied to his image, romanticized though it may be.

Photo courtesy of Inquirer.net

Weapon of choice

Another common symbol in typical depictions of Bonifacio is the bolo, raised in defiance. Was it really his weapon of choice?

In his book A Question of Heroes, Nick Joaquin offers an explanation behind the significance of the bolo to the Katipunan. While there are disputes over dating key events that led to the Revolution (the Cry of Balintawak, Cry of Pugad Lawin, the tearing of cedulas), they all seem to have occurred around a specific religious celebration in Malabon.

Joaquin writes: “[St. Bartholomew’s] images carry a large sharp knife, the instrument of his martydom… The saint with the knife is the patron of Malabon town, where he has, through the centuries, like all our patron saints, acquired a Filipino look. He carries a native bolo, for one thing, and on his feast day the main street of Malabon becomes two dense rows of impromptu stores where one may buy blades of every size and kind… A school of thought insists that the KKK proclaimed the 1896 revolt on the eve of St. Bartholomew, Aug. 23, and the bolo-wielder of Malabon certainly aided the bolo uprising: Katipuneros from the provinces found it that much easier to pass through the Spanish lines and congregate in Balintawak because they had the excuse of being on their way to attend the fiesta of San Bartolome de Malabon.”

With the significance of the place to the story, and the circumstances surrounding the timing of the historic events, it’s unsurprising that the bolo persisted as the symbolic weapon of the Katipunan.

To be fair, though, other sources state Bonifacio also wielded a revolver.

Andres Bonifacio, the Supremo

As one of the most renowned leaders of the Katipunan, it is but natural that Bonifacio became known for his bravery. His strong beliefs and intense dedication to the fight for freedom have undoubtedly enthroned him in the pantheon of Philippine heroes.

As the poster-boy of mass resistance, he may very well be the reminder that anyone can contribute to a noble cause—that you don’t have to be at top of the social heap to influence change in it.

But what most forget—or perhaps don’t know—is that there is another side to Bonifacio. His attitude and impatience, especially in the early stages of the Revolution, was what some see cause for his eventual undoing.

Joaquin likens the story of the Revolution to that of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, in which the sorcerers brewing an experiment in the cauldron are the propagandista ilustrados, and the apprentice that stirs (and ruins) it before it is ready is Bonifacio.

The facts: The Katipunan, led by the Supremo in Manila, failed. Following the loud cry it made at its birth, the Revolution took its first steps in the hills of San Juan—and stumbled. The battles the Katipunan won weren’t in the “capital” but the provinces. Joaquin sums it up thusly: “The Katipunan was of Manila, but the Revolution was of Cavite.”

Bonifacio went to Cavite in December 1896, but he made a mistake. Instead of uniting the Magdiwang and Magdalo factions, he chose to take sides. Unfortunately for him, each side made their own choice, too, and it was against him, the non-Caviteño, the outsider. Hence his loss at the Tejeros Convention, to Emilio Aguinaldo, the Caviteño who wasn’t even present at that time.

It turns out the Supremo’s influence wasn’t as supreme, after all.

–

Today is the eve of the auction of historically important documents such as the Acta de Tejeros (Tejeros Proclamation) and Acta de Naik (The Naik Military Agreement)—both signed by Bonifacio, as well as the Heneral Luna telegram. With that, it’s important to remember the significance of studying history. Beyond knowing the whos, whats, and whens, it’s about realizing and thinking of the now-whats.

It’s only with the knowledge of what went before that we can truly progress as a nation. But if we don’t even have the documents and artifacts as landmarks to help us trace the paths of our history, how can we chart the way forward?

Get more stories like this by subscribing to our weekly newsletter here.

Read more:

Aguinaldo’s deadly telegram to Heneral Luna emerges in auction

Congress has little time left to create a Department of Culture

Bonifacio’s flag was auctioned off for P9.3 million—should we have allowed it?

Read more by Pauline Miranda:

Who has the power to claim historical cultural property?

To stop repeating history, we have to relive it—in VR

Jose Rizal might not be the hero we always thought he was

Writer: PAULINE MIRANDA

ART MARX REINHART FIDEL