There are two kinds of plant collectors: one who collects them for the inherent aesthetic value they lend to their space, and another who believes in the practical air filtering abilities of plants. This is obviously a false dichotomy; there are people who collect plants for luck, too. And then there’s Bacolod-based artist Kris Ardeña.

After living in the US, Madrid, Luxembourg, Germany (he speaks English, Filipino, Spanish, Cebuano, Ilonggo, and a few other languages), Ardeña currently shares a 200-sqm home/gallery/workshop with his band of creators, his paintings, and his plants.

“BTW, I don’t consider myself a collector of plants. I’m more for their emo aesthetic quality,” he opened our exchange over Instagram direct message. “The plants I have are common outdoor plants. (They) evoke more the psychology of familiarity.” Some of his favorites are begonias for their colors and variety; agave because it reminds him of the beach house he grew up in; and palms for the tropical feeling they evoke.

“I don’t consider myself a collector of plants. I’m more for their emo aesthetic quality… (They) evoke more the psychology of familiarity.”

The artist was quick to clarify, however, that his indoor garden was in no way triggered by the pandemic. “It was already planned before: the papag, the plants. Nature is inevitable in the rural tropics, so it becomes integral, but not something I necessarily seek.”

The papag he’s talking about is the Filipino version of a bed made with splintered bamboo panels and sometimes coco lumber legs. It can be laid with banig for sleeping. In Ardeña’s case, it’s an integral part of his studio setup, designed to mimic the elevated entrance to a nipa hut.

Occasionally the papag is a platform for his shrubs, vines and small trees (he has an indoor potted palm and a malunggay tree) in the living room—although there’s hardly any room to speak of. He tore down the walls to create an open plan, with space transformed depending on his needs; his bedroom, for example, is hardly a space for sleeping as it is an exhibition space and a backroom for his works.

‘Why paint plants’

“The plants form part of what we do; it ties into the philosophy of how I create,” he said.

How does an artist like him work then?

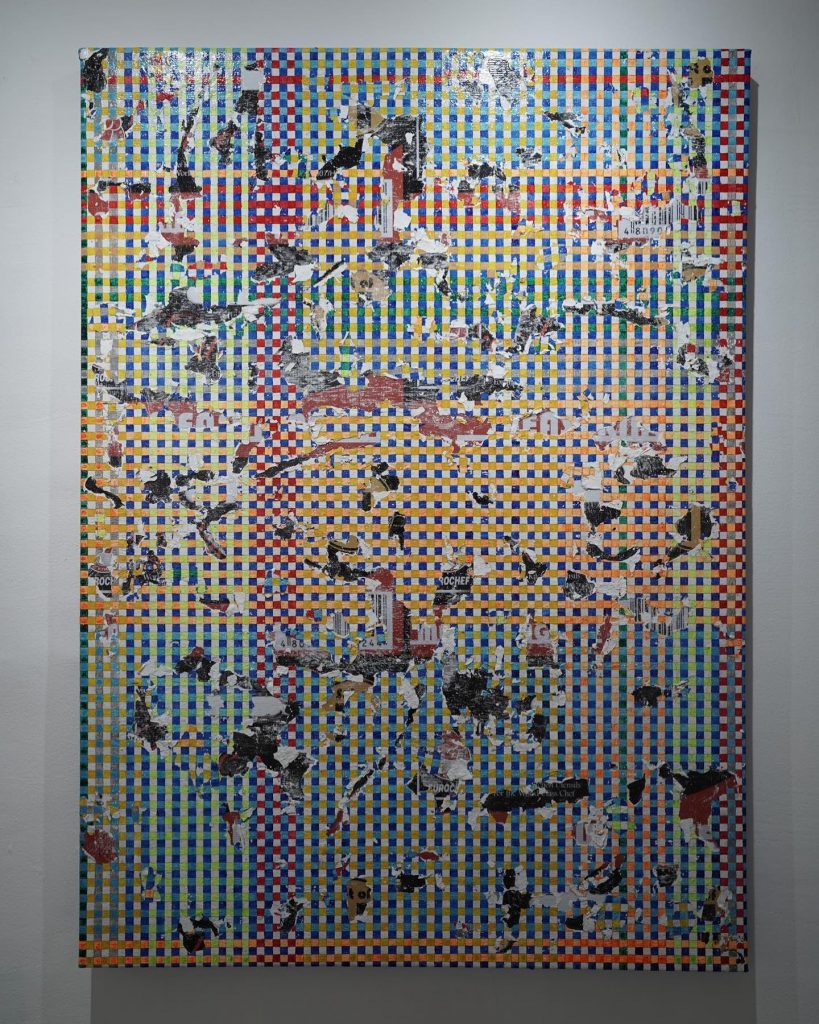

For those who know his oeuvre, Ardeña is most recently known for his bigger than life paintings of the ubiquitous Filipino household object basahan, a floor rag woven out of scrap fabric.

Before the lockdown, Manila’s art crowd got a glimpse of these six-foot-tall cracked tarpaulin paintings at Tropical Future Institute’s booth at Art Fair, where it was exhibited along with everyday Filipino objects like the pabitin, a suspended bamboo trellis with snacks hanging from it, which is a staple at children’s birthday parties and fiestas.

A year before that, these “ghost paintings”—referring to the application of several layers of paint to a surface and allowing them to crack like the walls of tropical houses that humidity transforms from a once smooth surface to a textured one—were exhibited at the annual Art Dubai international art fair.

“It’s a material that’s readily available to me where I am right now,” Ardeña said of the basahan series in 2020. “It was just there and that’s why I use it. That’s the ingenuity of adaptive reuse. It’s not about recycling, it’s about the possibility of the material itself.” It was not to reproduce cultural symbols as new tropical aesthetics or even to evoke a feeling of nationalism. In the same interview about his Art Fair paintings, he was quoted as saying, “To claim a national identity as an artist is limiting and insular. My identity is more complex than that.”

Those paintings take time and lots of hands to make. For a 7×10-ft painting called “Macho Dancer,” it took Ardeña and his team eight months to fill the whole woven PVC fiber canvas with 2×2-cm squares of the basahan. His latest work, a 7×10-ft painting patterned after the Ilocano binakol weave, takes this exercise in patience to the extreme with 0.3 cm squares.

To paint a leaf can be just as powerful as a whole discursive post-conceptual work full of information about…. I don’t know? the coronavirus, for example.”

The potted plants in his studio aren’t just for aesthetics but also for meditation. “You get lost here in time [as you work] because (the space) is calm and peaceful.”

As if to reinforce this thinking, he recently posted a self-interrogatory question on Instagram: “Why paint plants? Because it accumulates time.”

To him, plants also serve a tangible purpose, as in he literally uses leaves among other plant parts as part of his work while drawing inspiration from them.

On his Instagram profile are a few works from banana leaf etchings like a skull drawn for leisure and a piece of green scribbles on a painted white canvas. “What do you do with leftover anahaw leaves?” he asked in one post. “Incorporate them in your painting.”

In another post, he shared an in situ of one of his cracked paintings pinned to a papaya tree growing in his neighborhood. The unsuspecting fruit-bearing trees are owned by his neighbor’s wife.

His most recent post as of writing is a bunch of dried acacia leaves shaped like a cork, presumably related to a new work: a block covered in gumamela leaves.

But do not be fooled; his identity as an artist is more complex than plants. He’ll be the first one to point out that his work—even his earlier ones—is not wholly influenced by these living organisms. “I don’t like to work with specific themes in my work. Puff, how boring.

“I want to allow themes to be embodied in my work whether formally in the technique or in the material aspect, not necessarily within the thematic approach. To paint a leaf can be just as powerful as a whole discursive post-conceptual work full of information about…. I don’t know? the coronavirus, for example,” he said.

The social and anti-social uses of plants

It turns out he is also the second kind of plant collector I described previously. He hates air conditioning and in a way, the plants make the air circulate throughout his space, reducing the need for mechanical ventilation. In fact, his whole 200-sqm studio only uses three electric fans and consumes only P1,000-worth of electricity a month. He joked that his internet bill costs much more. Welcome to the Philippines, I said, where slow internet connection costs a fortune.

Ardeña has been living in his open-plan space with its nine-foot ceiling, matte white walls (which make for a good test hang background as they absorb light), and a decent amount of natural lighting for two years now. But so far, he has enjoyed working with other painters whom he recruited from neighboring towns. “I like my crew. We hang out, drink together, barbecue on the rooftop. There are always cases of beer and wine in the studio.”

There’s also his famous neighbor: a handicraft place called Artisana Island Crafts. It’s pretty legendary, he told me. “In the ’70s, José Joya, Ang Kiukok, and a bunch of other artists came to Bacolod to do ceramics there.” He said he likes to work there sometimes because the people are nice.

He’s generally a sociable person. But on the flip side, one of the reasons he chose to reside in downtown Bacolod—200 km away from his hometown Dumaguete—is because of the anonymity it affords him as an outsider. “Because I am not from here, there’s no gossip, no s**t. I am left alone to work,” he said. “Pinoys love to gossip. I prefer to socially isolate especially from the art people here.”

(Other than that, Ardeña said he loves it there because “I always get energized by the creativity of what I see every day, the ingenuity and the driving force of people who may have very limited resources yet are able to make a thing of beauty.” He has an ongoing photo series called #BalayTropikal that catalogs Bacolod’s street views.)

In a sense, these plants are his company in days of isolation, while serving as a shield from watchful eyes. He dreams of living in a space surrounded by lush tropical vegetation “and far away from gossiping art people,” much like American architects Jacob and Mellisa Brillhart’s tropical modernist bungalow residence in Miami.

But hiding in his own man-made forest would be counterproductive, since some of his plants come from his neighbors, like the ternate (butterfly pea) and the pandanus (the big one used for weaving, not for cooking). He’s currently waiting for a 30-year-old coconut tree bonsai being grown by a friend who lives nearby. It’s expected to arrive around May or June.

“Once we get that in, then we develop the entrance papag setup. It would be crazy to bring that big coconut inside,” he said.