I’ve tried many coping mechanisms over the course of quarantine—with varying levels of success.

I’ve started cooking—for myself then eventually for work. That was pure joy, but since I had to do it regularly I’ve since viewed it as additional stress. I’ve escaped to alternate worlds and finished three books so far but only because it was a way to lull myself to sleep during bouts of insomnia.

And then things take a turn for the worse a month in as I went on an online shopping spree. I’ve bought clothes from local brands, prints from art fundraisers, Japanese surplus ceramics from IG shops, and now hair care products because I’ve decided to grow my hair. It was, as Rebecca Bloomwood in “Confessions of a Shopaholic” said, fun while it lasted, while my bank account could sustain it. “But then it’s not [it can’t] and I need to do it again.”

I did all this holed up in my room only stepping out for meals. I did this while in my pajamas—sometimes not even, just whatever I could grab from my drawer (not closet) like loose-fitting tops relegated as “pambahay” and running shorts.

Gone were the days where every morning (sometimes, the night before) I would contemplate what to wear for work. The last time I pulled out a whole outfit was my last day in the office on Mar. 11. These days it’s just a formal top for video conferencing and running shorts underneath as cliche as that work-from-home meme is. On some days, I’d muster the energy to put on accessories, my favorite engraved necklace or my beloved pearls. Heck, I haven’t even washed my jeans since this quarantine started.

[READ: Not washing your jeans is the best way to save water this season]

I couldn’t help but wonder: Would it make any difference if I were to wear my work clothes while working at home? Will it make me feel better, alleviate stress? Bring a semblance of normalcy even if at times I work with my laptop in bed? Will it, to quote Marie Kondo, “spark joy?”

Feel-good effect

Carolyn Mair PhD, a behavioral psychologist and the author of “The Psychology of Fashion,” in a piece about the same matter I’m writing of now says, “When we work from home, it makes sense to maintain the routine of dressing ‘appropriately’ for our role.”

This enables us to take some control, she adds. This, in turn, reduces stress and can help us feel confident and motivated.

Others, like the New York Times’s chief fashion critic Vanessa Friedman suggests something more proactive. Rather than just putting on clothes, put them on neatly, tuck your shirt in, brush your hair, swap house slippers for shoes—all the things we’d normally do on our way to work (although, this situation we’re in is, of course, not normal).

“I need all sorts of maybe-silly signals to my brain that it is now in work mode instead of home mode. One way that is achieved is by walking out the door. The other is by creating rituals that have the same effect,” she said.

Social context collapse

Back in the “normal” times, Robin Givhan, fashion critic for The Washington Post, says, dressing up for work meant signaling who you are to other people, what you expect from your day, what you have on your agenda.

She adds, “I also think it is sort of a line of demarcation between our private time and our public time, our playtime and our work time. So I think it sort of gives you a sense of order to your day.”

But Sarah Spellings, another fashion critic (yes, you will hear a lot from them in this story), this time for The Cut, raises an important point: Without the context of the workplace, without “the other people” Givhan describes and without a place to be, clothing loses its social context.

“There’s nobody to dress up for: no boss to impress, no friends to see in person, no gyms to work out in.” Unless, of course, you spend most of your day on video conference, which counts for pseudo-interaction.

But just as the lack of context frees us from that obligation to present ourselves to others, Spellings continues that it could open up possibilities for self-fulfillment. “Just as easily, you can choose to put on your favorite outfit. There’s no code, so there’s room to play. Either extreme is acceptable,” she says. “This isn’t about productivity. It’s about pleasure.”

I am (valuable) me

I personally subscribe to Spellings’ last line there. While for Givhan, though it was not explicit, there was a suggestion that to dress up is to bring yourself up to time, to make yourself open, free for productive purposes.

But that is not to discredit her argument—after all, she writes in the context of working from home, where, of course, a semblance of productivity is required.

She writes on the onset of the work-from-home arrangements early in March, “We dress to indicate our skills—the lawyerly suit, the banker pinstripes, the tech cashmere hoodie. At the root of all those choices lies a plea—See my worth. Along with a full-throated declaration—I am valuable.”

But that has since dissolved as weeks in isolation rolled on. The discipline it took to stick to, say a three-piece suit to indicate you work in finance, has since dissipated. I know this because I live with a guy who works in banking. His office is our couch and the most formal piece of clothing I’ve seen him wear is a Uniqlo DryFit polo shirt with boxer shorts.

For someone who works in the creative industry as I do, there are no uniforms and signifiers to speak of, to differentiate you from the top tier (except maybe donning and wearing designer brands). Where I work, I could just as easily be mistaken for an intern. But that’s the fun in it. I could be whoever I want to be.

Since this quarantine, all I have been signaling to other people is a 20-something bummer, which is mostly true during most days when I don’t shave and given the state of my hair (I haven’t had a haircut in three months).

Let me end here with a quote from Givhan, who, in an interview with NPR’s Noel King, says, more than the muddling of time, something else is lost when we don’t perform our identities through clothes.

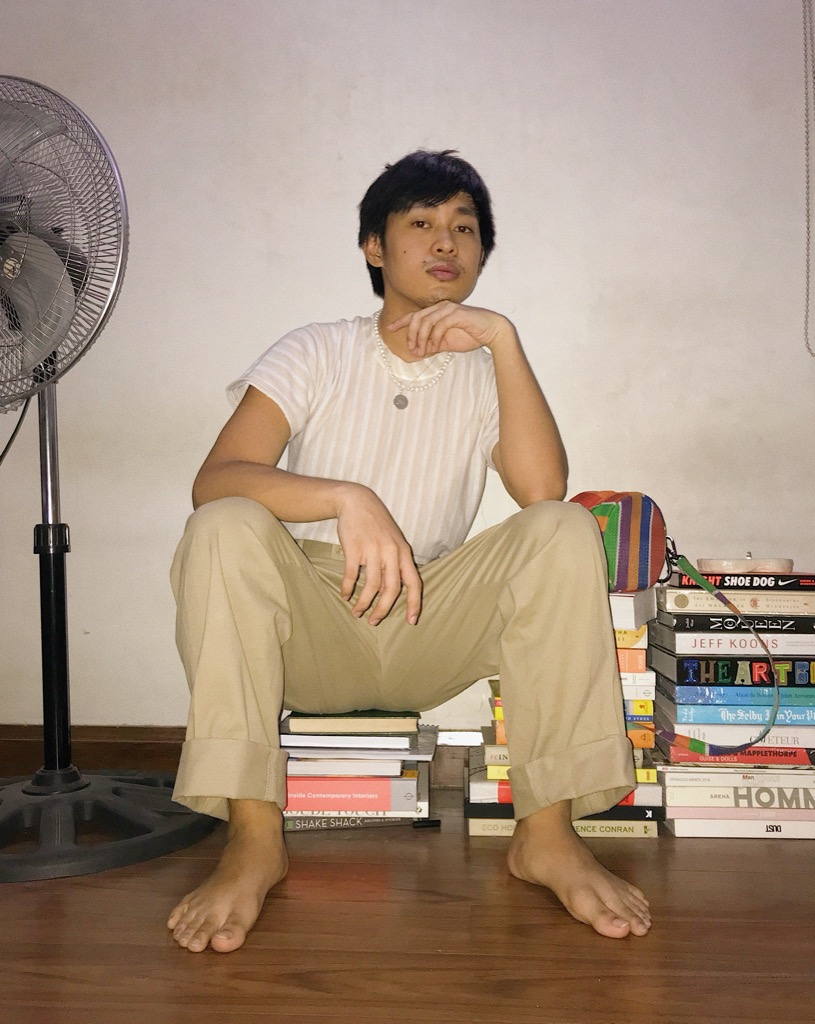

“I think that we’re going to lose a little part of ourselves, a little part of our individuality. I mean, what I think is sort of sad, particularly for younger people, is that we all go through a process of figuring out who we are. And part of that process is trying on different personalities. And we do that through attire. And I think that it just sort of becomes harder to figure out who you are and who you want to be and how you fit in when you don’t have that ability to sort of go out there and take on these different characters until you find the one that’s really you.” That was all it took for me to put on a decent outfit for the day.

Writer: CHRISTIAN SAN JOSE