As a child, Woldy couldn’t understand why they couldn’t just have barbecues like a typical American family instead of a stew cooked in a cauldron that could feed an entire block. “It was almost embarrassing for me to have this huge outdoor fire with the smell of wood burning and sizzling goat meat; I could only imagine what the neighbors were thinking.”

His mother’s side from Manila also migrated to the U.S., so Woldy and his brothers grew up having them around. He and his twin brother would spend afternoons at their grandmother’s, his lola lovingly filling bowls with champorado. He loved it, but still he was clueless as to why he had to have a “second lunch”—merienda in Filipino.

This is not a new feeling for children of immigrants trying to understand their parents’ insistence on embracing the culture of the land they left behind for the promise of America. “Food was her first line of defense against a deep and abiding fear of the Other,” writes Grace M. Cho in the food memoir “Tastes Like War.”

As in “Crying in H Mart” by Korean-American singer and writer Michelle Zauner, Cho, the daughter of a white American merchant marine and a Korean bar hostess, tries to “write her mother back into existence.” Korean culinary heritage is a bridge through which they reconcile their identities and that of their parents.

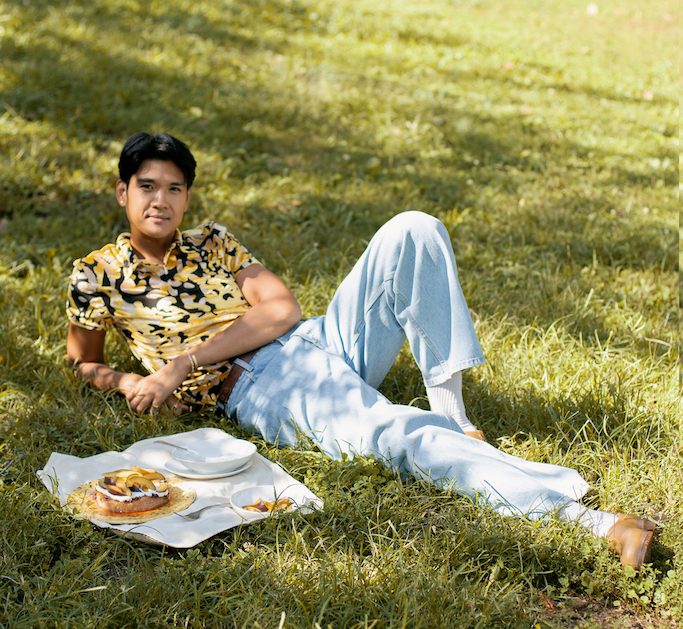

Woldy’s culinary rekindling didn’t occur until his 30s. By then he was coming to terms with not just his Filipino roots but also his hearing disability and his identity as a gay man.

It happened in 2019, in the company of fellow queer people who share the same love for food at an event called “Pride Table.” He served a reinterpretation of his late father’s calderetang kambing. But instead of steamed white rice, it came topped with a crisp fried rice wrapper typically used for spring rolls.

“Breaking it reveals what is me and what my food culture is,” he says, referring to cracking the rice crisp. “Coming through [the cracks] are these different bold flavors that are me; I am all of these different things.”

As a child, Woldy couldn’t understand why they couldn’t just have barbecues like a typical American family instead of a stew cooked in a cauldron that could feed an entire block. “It was almost embarrassing for me to have this huge outdoor fire with the smell of wood burning and sizzling goat meat; I could only imagine what the neighbors were thinking.”

His mother’s side from Manila also migrated to the U.S., so Woldy and his brothers grew up having them around. He and his twin brother would spend afternoons at their grandmother’s, his lola lovingly filling bowls with champorado. He loved it, but still he was clueless as to why he had to have a “second lunch”—merienda in Filipino.

This is not a new feeling for children of immigrants trying to understand their parents’ insistence on embracing the culture of the land they left behind for the promise of America. “Food was her first line of defense against a deep and abiding fear of the Other,” writes Grace M. Cho in the food memoir “Tastes Like War.”

Woldy’s culinary rekindling didn’t occur until his 30s. By then he was coming to terms with not just his Filipino roots but also his hearing disability and his identity as a gay man.

It happened in 2019, in the company of fellow queer people who share the same love for food at an event called “Pride Table.” He served a reinterpretation of his late father’s calderetang kambing. But instead of steamed white rice, it came topped with a crisp fried rice wrapper typically used for spring rolls.

“Breaking it reveals what is me and what my food culture is,” he says, referring to cracking the rice crisp. “Coming through [the cracks] are these different bold flavors that are me; I am all of these different things.”

“I knew that food was in me to tap into later,” he said in an interview in 2019. But he needed to see where his interest in fashion could take him. Eventually, years in the industry had him yearning for a change of environment. This is when his 180-degree pivot to cooking happened.

I constantly think of how I could remake it using seasonal produce.”

Woldy Kusina, a boutique catering company that prides itself on using seasonal and locally sourced produce, was launched in 2016. He started small, making fresh and vegetable-forward spreads of colorful crudites, herb-embedded frittatas, salads of blood oranges, and naturally-dyed hummus for friends’ intimate gatherings. Soon, he was creating designer banquets for fashion brands like Rebecca Minkoff, Christian Louboutin, Derek Lam, Moda Operandi, and MatchesFashion, with which he later collaborated on a pop-up café named after his business.

Photo by

Cristian V. Candami

Cristian V. Candami

New York publications then started catching up with Woldy Kusina. Gwyneth Paltrow’s goop included the caterer in its New York services directory, while New York Magazine’s The Cut named his caviar-and-avocado multigrain toast and fall-vegetable hash with butternut squash, Tuscan kale, oyster mushrooms, prosciutto di Parma, and soft-boiled egg, “breakfast foods worth serving at a black-tie wedding.”

“When I’m thinking about the things that I grew up eating, I constantly think of how I could remake it using seasonal produce,” he says. “Knowing that Filipino dishes are very hearty and meaty, I try to find vegetables that are also hearty. And I obviously love color so I try to bridge the two together.”

A year later, he did a rainbow rendition of pancit with colorful radishes (purple ninja, watermelon, daikon, Chinese rose), garlic chives, and confetti flowers for good measure.

The question of whether his take on Filipino cuisine is authentic or not is never lost on Woldy. Migrant cooks, after all, tend to be most riddled with the dilemma of representing “real Filipino food,” as the late Clinton Palanca wrote.

“I had that sort of internal struggle like, ‘Is this really Filipino?’ But then again, I am Filipino-American and I think I’m bridging those two together,” he self-assesses.

Photo by Noah Fecks

This improvisation is on full display at his kamayan series that started in late 2019. It’s based on the Filipino communal way of eating on a banana leaf laid with steamed white rice and a variety of viands, from roasted vegetables and seafood to saucy stews and hearty soups. While it is popularly known here as “boodle fight,” Woldy went with the term “kamayan” as it translates to a more amicable eating experience. “With boodle fight, is a fight going to happen?” he jokes. (The term did originate from a military tradition, so who knows?) Plus, it is nowhere near your typical boodle fight spread.

Banana leaves were piled with adobong hen-of-the-woods, cauliflower Bicol Express, kabocha squash kare-kare and lumpia. All these were served over spice-infused steamed rice. For dessert, Woldy’s frequent collaborator, gluten-free baker Lani Halliday, made small bibingka topped with edible gold, peanut brittle, and guava cream cheese.

The kamayan dinner landed a T Magazine review and praise from Filipino-Hawaiian food and culture critic Ligaya Mishan, who called it “thoroughly modern.”

their Kamayan dinner

in February 2020

“I remember the hotel’s general manager calling me as I was getting ready for the dinner to ask if I want to still do it but have hand sanitizers on the table,” Woldy recalls. “I’m like, ‘Let me just think about it.’ I worked really hard to create this Filipino food cultural experience and it’s plant-based, but at the time, I didn’t understand the severity of what was happening. I decided to just cancel it because I thought having hand sanitizers on the table took out the romance of that part of eating.”

Jeepney’s feast on banana leaves is closer to the kamayan experience in the homeland, with familiar forms and flavors and none of the plant-based alternatives. Think rice with tocino cured in 7Up, longganisa, and pork stewed in “a fascinating chocolate-colored sauce of beef blood,” as per food critic Pete Wells’ review.

Then there’s queer Filipinx chef Silver Cousler, the mind behind what would be Ashville, North Carolina’s first Filipinx restaurant, Neng Jr.’s. In February this year, they partnered with cook and writer Alison Roman for a boodle fight in Savannah, Georgia, which doubled as a fundraiser for their restaurant.

are in charge.”

For Woldy, it’s high time queer and people of color are given the long-overdue credit for their food cultures that white men have profited off of. “We’re trying to break the door, break the ceiling to create more of a safer space for people like us to thrive and be in without being suppressed,” he says. “That’s what’s happening now. I think being visible and sharing our story is important so that we can change the traditional white man-run kitchen into something where more people of color are in charge, and it’s hopefully a safe environment for work in, too. That’s what I’m hopeful for.”

This includes Lani and pastry chef Eric See. They all had their start at a community kitchen for food start-ups called Brooklyn Food Works, which is now Pilotworks Brooklyn after it was bought out in 2018. The change in management left the businesses it used to shelter without a place to operate. Eric decided to get their own space, which became Ursula, a New Mexican café in Brooklyn. Woldy was one of the LGBTQ+ guest chefs he invited. “I thank him for that, that he was able to save my business,” he says.

Up until the easing of restrictions in the city, he was unable to do catering with social gatherings on hold. What he did instead was pay it forward to his community. He’s made meals for folks at Ali Forney Center, a non-profit providing shelter and healthcare services to underprivileged LGBTQ+ youth. He also organized food drives for health frontliners, making sustaining and vibrantly-plated meals, like pancit with creamy sesame ginger dressing and a chicken adobo and portobello mushrooms sub.

If he’s not there, you can always find him on TikTok, dancing to his divas in the woods, on the road after a run, or in the kitchen in full chef regalia. On Instagram, along with his decidedly New Yorker style (quilted Bode jacket! Eckhaus Latta graphic top! J.Crew basics, of which he was once its campaign star!), his culinary creations are hard to miss. These include his various takes on the classic Filipino kakanin bibingka.

His bibingkas are as flamboyant as his fashion banquets. Decked in seasonal produce, he’s made the rice cake in a number of forms: petit fours, pan sheet cake, glazed birthday cake with fruit toppers, loaf wrapped in a blanket of banana leaves. His latest was featured on Bon Appétit, vegan and gluten-free bibingka waffles topped with fresh fruits, toasted coconut flakes, and coconut yogurt. (The traditional recipe calls for eggs and butter, which he substituted with club soda and coconut oil.) It was a dream come true for Woldy to be featured on a revered food publication, and sort of symbolic, too, he adds. “I’m a fan of Bon Appétit. My first [published] recipe is obviously a hybrid of Filipino and American and calling it bibingka waffles is something that’s cool to see.”

What’s next on his mission to bring bibingka to the fore? He’s toying around with mixing cassava and glutinous rice flour, an ode to another pastry creation of his mom. “I’m putting fresh fruit on the bottom of the pan and then inverting it,” he says. “Basically, it’s a take on my dad’s favorite cake, the pineapple upside-down cake.”

He’s also tinkering with using fig leaves as a vessel for bibingka in the absence of banana leaves. “You can actually eat the fig leaves!” he says. “I think that also creates that sort of new but familiar [feeling]. My brain is always thinking of other ways to make Filipino food even more interesting and progressive.”

His bibingkas are as flamboyant as his fashion banquets. Decked in seasonal produce, he’s made the rice cake in a number of forms: petit fours, pan sheet cake, glazed birthday cake with fruit toppers, loaf wrapped in a blanket of banana leaves. His latest was featured on Bon Appétit, vegan and gluten-free bibingka waffles topped with fresh fruits, toasted coconut flakes, and coconut yogurt. (The traditional recipe calls for eggs and butter, which he substituted with club soda and coconut oil.) It was a dream come true for Woldy to be featured on a revered food publication, and sort of symbolic, too, he adds. “I’m a fan of Bon Appétit. My first [published] recipe is obviously a hybrid of Filipino and American and calling it bibingka waffles is something that’s cool to see.”

What’s next on his mission to bring bibingka to the fore? He’s toying around with mixing cassava and glutinous rice flour, an ode to another pastry creation of his mom. “I’m putting fresh fruit on the bottom of the pan and then inverting it,” he says. “Basically, it’s a take on my dad’s favorite cake, the pineapple upside-down cake.”

He’s also tinkering with using fig leaves as a vessel for bibingka in the absence of banana leaves. “You can actually eat the fig leaves!” he says. “I think that also creates that sort of new but familiar [feeling]. My brain is always thinking of other ways to make Filipino food even more interesting and progressive.”

Cover photography by Nikki Ruiz

Creative direction by Nimu Muallam

Art drection, layout and design by Levenspeil Sangalang

Read more related stories